cw: discussions of suicide, racial violence, hate crimes

For quite some time now, it’s felt like we’ve been living in the end times. Check the news, your Twitter feed, the bookshelves of the YA section—it’s all dystopias and apocalypses, islands of plastic and radioactive waste that will not dissipate for a million years at least. It’s the end of the world as we know it, and no one is feeling anything remotely close to fine.

I know that. I know that the ice caps are melting and the tigers are running out of habitat, that we are in the middle of a mass extinction event and that in fifty years our everyday luxuries—plentiful chocolate and cheap coffee and Florida oranges in the middle of winter—may be mere memories. I know that there is a great deal of suffering that awaits us in the future and that, despite our best efforts, there will be only so much we can do to alleviate it.

I worry, nonetheless, about the absolutist ways in which we frame global catastrophe. There is, I’ve noticed, a streak of deep nihilism in talking about climate change—well-deserved nihilism, perhaps, but one which still worries me. In some places, it feels like even suggesting the idea of hope can get you labeled as willfully naive, an ostrich blissfully burying its head in the sand to hide from reality. You poor, naive soul—you think there’s still a chance that the world will be merciful, that you will live on? It’s time to face facts, and all the reports are telling us that we’re doomed.

Under reports about the unsustainability of our planet in fifty years, I see people discussing contingency plans and worst-case scenarios. If things are bad, I read strangers commenting on Twitter and Youtube, and if they’re only going to get worse—then how do I know (how will I know) when it’s the breaking point, when I can reasonably give up? Living through the collapse of modern civilization is a harrowing prospect; with so many reports alleging the inevitable death of the human species, is it any wonder that some people would want to decide their own suffering? When you have no home and money and the future looms like a void, what sense is there in holding on for the tenuous hope of change? With Nazis on the horizon and a lifetime of illness and suffering weighing on her, can we blame Virginia Woolf for choosing to drown?

Like all decent people with a shred of empathy, my instinct when faced with other people’s despair is to argue, to comfort. I want to say all the usual platitudes—that there are resources, hotlines, people who would need and miss you even then at the end of the world. That nature is resilient, and that even if we lose chocolate and pandas and processed sugar, there will still be things worth living for—small joys, dandelion fluff and spring clover and squirrels who walk up to you for offerings of bread and nuts.

It’s hard, though. It feels ingenious to talk about the beauty of life when I too often find myself falling into despair, traveling down nihilistic paths of what-ifs. There are a lot of things to worry about these days, and the coming future hardly seems any more stable. Counseling resilience and hope for others feels unbelievably presumptuous and insincere when there are days that I can do nothing but lay in bed, worrying about forest fires and nuclear winter.

And yet, despite everything, I want to believe in hope, in a future built on the slim chance that we are not yet fully doomed. I want to live, and I want my friends to live.

For someone who spent much of their adolescence in a miasma of low-level despair, this has been a rather unexpected shift of attitude for me. I was an unhappy, cynical teenager, obsessed with death and self-destruction—never enough to actively act on it, but enough so that I still remember what it feels like to see the world as nothing but a yawning black hole, an endless abyss into which all happiness would vanish. Even today, I am skeptical of inevitable happy endings, the idea that so long as you make it out of adolescence, it will all get better—that the moment you turn eighteen or move out of your small town, you will find yourself bright and shining on the other side of happily-ever-ever. It gets better for some of us, yes. It gets better, yes but not always, and not for everyone. It gets better for a day, a month, maybe whole years at a stretch, but the world has never promised any of us happiness, only the certainty of silence and death.

Yet I think there’s still value in fighting for something finite, something that will necessarily end. I think of New York City in the 80s, the men who cared for friends and lovers through the height of the HIV epidemic. Was the time they spent ultimately in vain, rendered useless by the fact of death? Or is there still value in that kind of care—care without grand ambition of cure or eternal repair, care that only hopes to better things for today and for now?

I think of N. K. Jemisin’s assertion that “an apocalypse is a relative thing,” the fact that for many people—indigenous peoples dispossessed from their homes, Black peoples forced from their homelands into slavery—the end of the world has already come. Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale offers a harrowing vision of a patriarchy, but as other critics have pointed out, the violence Atwood describes is all too real for Native and Black women. So many of the symptoms we associate with dystopia—famine, violence, a stark disregard for human life—are in fact already present in even supposedly civilized countries, just a few feet away from Whole Foods and microbreweries. As anti-trans legislation continues to be passed and ICE separates children from their families, it’s so easy to give in to look at the state of the world and give into despair.

And yet every time I go out to engage with my various communities, I’m inspired by the strength I find. When the world is literally built against you, it is so easy to give up, and yet there are so many people who do not, who continue to fight against the despair of a world built to erase their existence. I don’t want to fetishize the strength of marginalized communities—Black women shouldn’t be expected to be constantly “strong,” and abuse survivors are no less valid for being angry or scared instead of brave and inspirational. Still, incurable optimist that I am, I can’t stop myself from thinking of the way resilience persists even under the most dire conditions. Like dandelions growing through sidewalk cracks and matsutake mushrooms growing in the wake of nuclear disaster, kindness and empathy are hard to truly kill.

I think of the Japanese pensioners who, in the wake of the nuclear meltdowns at Fukushima Daiichi, volunteered to help with the radiation cleanup. In their sixties and seventies, they argued that they, and not Japan’s youth, should bear the risk of radiation exposure. “We’re doing nothing special,” volunteer Masaasaki Takahashi told reporters in 2011. “I simply think I have to do something and I can’t allow just young people to do this.”

I think of the documentary Babushkas of Chernobyl, of old women who sing folk songs and make jam from irradiated berries and leave mushrooms for the hedgehogs in the winter. Because species of fungi can feed on radiation, an on-site scientist tells the filmmaker watchers that even mushrooms gathered from safe zones can absorb high levels of radiation. But against the prospect of starving during the winter, what other fate are the hedgehogs meant to choose? If the hedgehogs must live short, irradiated lives, are they still not worthy lives nonetheless?

I think of Old Friends Senior Dog Sanctuary, the love that millions of internet strangers willingly invest in these animals that, to many, are already damaged goods—too old, too sick, too doomed. A bad investment, one that will give out after four or five years at most. I think of the dogs themselves—Leo and Gracie and Captain Ron and Gertrude, all so happy, all so loved. Blind and tri-pawed and arthritic, they did not live in fear of death, did not spend time on pity and trembling in the face of their own impending demise.

Tomorrow I could be hit by a car in traffic or struck by a sudden freak asteroid; tomorrow my heart could decide to stop, some blood vessel in my brain burst after years of hard service. I have been lucky; I have healthcare, a relatively stable income, and the luck to live in an area of the world with easy access to clean water and modern medicine. Yet I know that all of this is fragile, infinitely contingent and provisional. Tomorrow, someone could set my apartment and all my belongings on fire; I could trip while walking down the stairs or fall sick and lose all my savings in attempting to navigate the US healthcare system.

For now, there is sky and grass and a content cat napping on my bed. For now, I am alive, and so are you, and billions of people as well, many of them suffering the same or worse than I am. For now, I can leave out bread for the birds and nectar for the hummingbirds, pick up plastic where I see it and participate in mutual aid instead of hoarding against an unknowable future. Maybe these are ultimately all small gestures; maybe they will only be helpful for a few hours or days, the way fallen baby birds so rarely survive even under the best of care. That does not make the work any less important.

As Robin Wall Kimmerer writes in Braiding Sweetgrass, “Even a wounded world is feeding us. Even a wounded world holds us, giving us moments of wonder and joy.” To respond in kind with joy then is not naivety, but a returning of the gift that the world has given us. If either my life or death is to have any meaning, this is how I want to live—giving joy to others, making use of the time I have to make the world a little kinder for the ones I share it with.

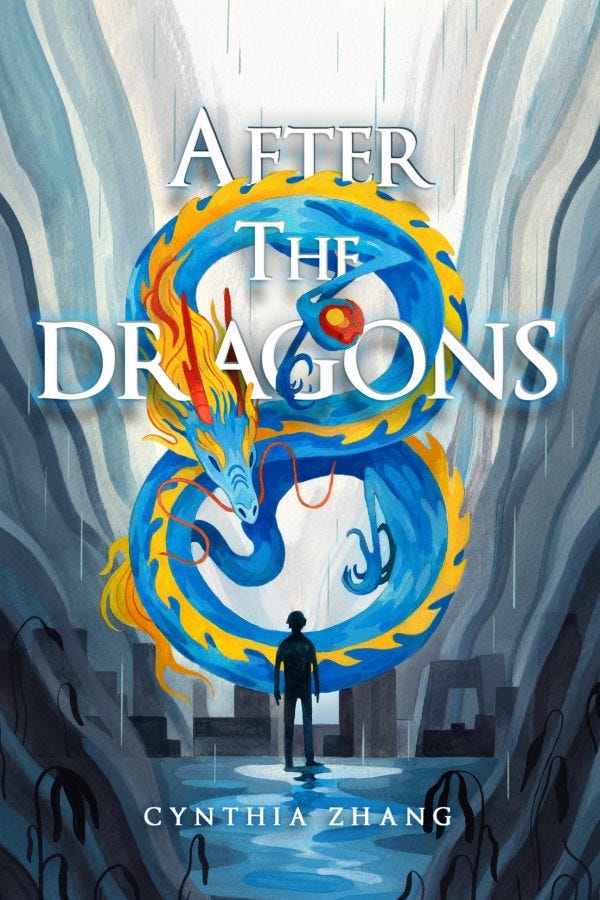

Find out more about Cynthia’s queer science fiction novel After the Dragons here.

Dragons were fire and terror to the Western world, but in the East they brought life-giving rain…

Now, no longer hailed as gods and struggling in the overheated pollution of Beijing, only the Eastern dragons survive. As drought plagues the aquatic creatures, a mysterious disease—shaolong, or “burnt lung”—afflicts the city’s human inhabitants.

Jaded college student Xiang Kaifei scours Beijing streets for abandoned dragons, distracting himself from his diagnosis. Elijah Ahmed, a biracial American medical researcher, is drawn to Beijing by the memory of his grandmother and her death by shaolong. Interest in Beijing’s dragons leads Kai and Eli into an unlikely partnership. With the resources of Kai’s dragon rescue and Eli’s immunology research, can the pair find a cure for shaolong and safety for the dragons? Eli and Kai must confront old ghosts and hard truths if there is any hope for themselves or the dragons they love.

Cynthia Zhang is a Ph.D. student in Comparative Studies in Literature and Culture at the University of Southern California. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Kaleidotrope, On Spec, Phantom Drift, and other venues. She is a 2021 DVdebut mentee and is on the web at czscribbles.wixsite.com.